The world has celebrated rinderpest virus eradication. But an FAO video shows there’s cleaning up to do after the party. Virologist Michael Baron explains.

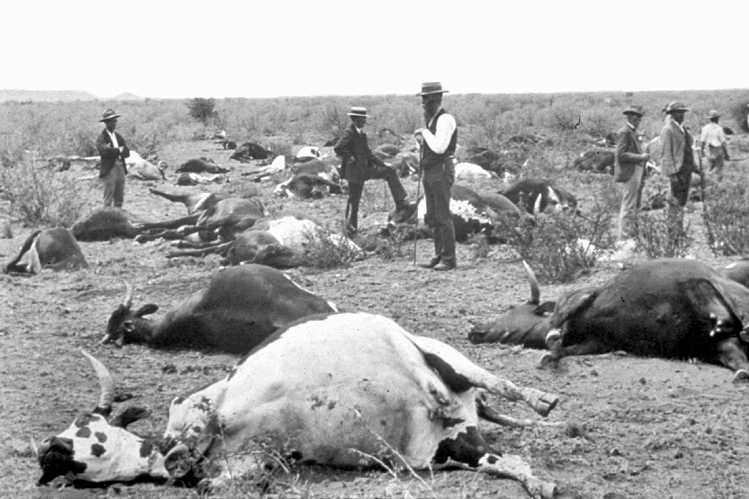

Rinderpest, aka ’cattle plague’, was with us for a long time, at least 2000 years. Over the centuries, the virus killed uncounted millions of animals in Asia and Europe. When it was accidentally introduced into Africa for the first time, in the late 19th century, it went on to kill ~90% of the cattle and buffalo on that continent. It was, let’s be honest, a Very Bad Thing.

Note the past tense. After several decades of hard work across all of Africa, the Middle East and Asia, rinderpest was declared eradicated in 2011 (PDF), and there have been no cases of the disease, anywhere, for more than 15 years. Rinderpest was a Very Bad Thing, but it is now no longer a thing at all.

This was a great achievement. It is only the second viral disease ever eradicated, following on from the elimination of smallpox from humans in the 1960s and 70s. The global veterinary community, particularly FAO and the OIE, which coordinated the eradication efforts, felt justifiably proud. As did scientists across the world who contributed to the eradication efforts, including former colleagues at The Pirbright Institute (then the Institute for Animal Health) who developed important diagnostic techniques.

A deadly challenge: Keeping the world free from rinderpest

In the post-eradication era, rinderpest virus containing materials are found in more than 24 laboratories worldwide posing risk of reintroduction. This video shows FAO supporting countries in the process of destruction and sequestration of the virus and advocates for the same practice in other member countries.

However, just as was the case with smallpox, when all the celebrations and the back-slapping died down, there was still the clearing up to do.

Know thine enemy

Both smallpox and rinderpest had been extensively studied while they were being fought, and the viruses existed in many laboratories around the world. No one dared to immediately destroy all the remaining samples – what if we were wrong about eradication, and the disease came back? What if someone was keeping a secret stock that they used as a bio-terror or bio-warfare agent?

Some material would need to be kept, and scientists kept trained, as a hedge against these possibilities. The question facing everyone was what to do with these remaining materials so that there was no risk of the virus being accidentally released. There are still people who remember the escape of smallpox virus from a laboratory in Birmingham in 1978, a year after the last natural case of the disease.

The answer was to set up a system whereby specific laboratories could be inspected and approved as secure enough to hold rinderpest virus, and encourage everyone to put any remaining virus in those places. The African Union (AU) were quick to adopt this aim, agreeing in 2010 that any rinderpest virus in Africa had to be either destroyed or stored in an approved high-security facility maintained by the AU in Ethiopia.

Over 2016, a number of countries have done this, notably Botswana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and Sudan. As seen in the video on this page, in order to be sure that there are no accidents when doing the clear up, several countries invited the FAO to send a team of experts to help with destroying what was not required and securely shipping the valuable samples for storage.

The price of peace is eternal vigilance

Laboratories in the developed world have either destroyed their rinderpest or applied for their high security laboratory to be approved. One of the first to be so approved was the BBSRC National Virology Centre, which is housed in the Plowright Building, a new high containment laboratory facility at The Pirbright Institute (see this double video feature for more); the institute receives strategic funding from Global Food Security partner BBSRC. Co-incidentally, the Plowright Building is named after Walter Plowright, who developed the rinderpest vaccine used in the eradication campaigns, and provides both high biological containment and high physical security.

As well as providing a secure store for rinderpest, such a facility enables us to maintain our preparedness for future threats to UK livestock. In addition to the continuing threat posed by foot-and-mouth disease there are new diseases: African swine fever and sheep/goat pox are already spreading into Europe while PPR, a close relative of rinderpest that affects sheep and goats, sits on its borders.

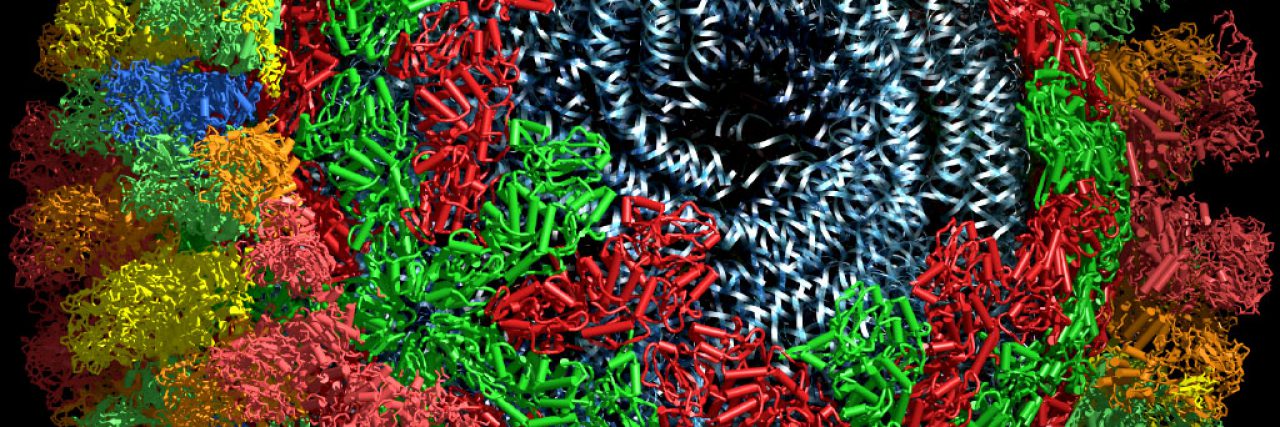

In the meantime, scientists at Pirbright have taken the lead in promoting the ‘digitising’ of rinderpest isolates to determine their full genome sequence. After sequencing, the viruses will be destroyed, eliminating the risk of accidental release. With modern technology, any isolate could be recreated directly from its sequence – if ever required – removing the need to keep the actual virus.

In the meantime, the FAO World Reference Laboratory for Rinderpest will be maintained at Pirbright where it has been based since 1994. It provides a global diagnostic capability in case anyone ever suspects an animal has rinderpest.

For both the old threats and the emerging ones, it is good to be prepared.

About Michael Baron

Michael Baron has worked at The Pirbright Institute for the last 20 years, focussing mainly on the basic biology of rinderpest and peste des petit ruminants (PPR), two important diseases of livestock affecting primarily animals in developing countries. He is currently Research Leader of the Paramyxo and Bunyavirus Group where he is working to develop rapid pen-side diagnostics and improved vaccines for PPR, as well as studying the basic biology of the virus.